Life might be telling Sunday Reilly she’s past her use-by date. But she’s not planning to go quietly.

‘It’s two months on a Greek island,’ I said, ‘working holiday, I’ve got the next draft of my novel to finish.’

‘The kids didn’t mention anything,’ he said.

‘That’s because they don’t know yet,’ I said.

Neither did I till that moment.

Cue me realising that this might just be the worst decision I’ve ever made.

You don’t know me very well yet, but believe me, that’s a very high bar.

Sunday Reilly has been many things. An author. A mother. A wife. A daughter. A friend. A lover. But that’s all about to change. Because, whether she likes it or not, Sunday is stuck on a hormonal steam train that’s smashed through everything she thought she knew about herself. And she can’t find the emergency brake.

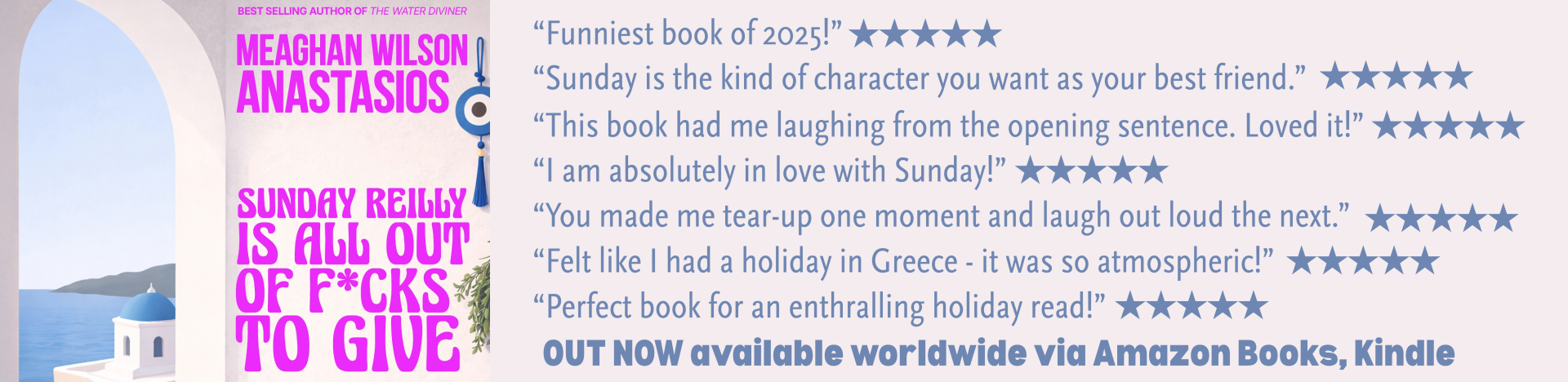

“Sunday is the kind of character you instantly want as your best friend.”

“Funniest book of 2025. 5 stars!”

“I am absolutely in love with Sunday! This book is one of those rare gems that makes you laugh out loud on public transport and not even care who’s watching.”

“This hilarious tale will resonate with all women.”

“Has you doing pelvic floors and weeping with laughter!”

“Sunday is the kind of character you instantly want as your best friend—flawed, funny, real, and so incredibly relatable.”

“I am absolutely in love with Sunday!”

This is Sunday’s story as she upends her life and takes off for the Greek islands on a whim in search of adventure and romance. She figures her life is halfway done anyway, so what has she got to lose?

Nothing goes to plan, which for Sunday has become par for the course. What was meant to be a retreat to work on her new novel becomes something else altogether as she pursues creative and romantic inspiration in one of the most beautiful corners of the planet.

As she barely makes it through a string of riotously funny near disasters, Sunday picks up the pieces and learns to embrace a new kind of freedom. A journey that was meant to be a distraction from truths she would rather forget becomes an opportunity for transformation as she embarks on a new phase of life.

SUNDAY REILLY IS ALL OUT OF FUCKS TO GIVE is funny, outrageous, angry, and heartbreaking, because life for women of a certain age is all those things. This is an uplifting and tender coming-of-age story for the middle-agers about the search for a new chapter in life full of love, meaning, and purpose after all those things have been stripped away.

Sold? Want to dive into the Aegean with Sunday right now? Off you go, then! Pack your bags, don’t forget sunscreen, and click here.

Want to try a few chapters for free before committing?

Fair enough. Here you go. Download this. Come back when you’re done! And, enjoy the ride!